The official title of Session 102 was We’re Not the Destination, We’re the Journey: Revealing Archival Collections at the Web’s Surface. If you attended this session or don’t want to read through the details, you can skip to the end and just read my thoughts on this session.

California Digital Library

The first presentation was by Lena Zentall of the California Digital Library (CDL). I believe it was titled something like “Untitled <snappy name here>”. CDL is increasing visibility of primary sources by targeting primary sources to specific audiences. Lena described how they view the URL as a line to reel in new audiences. She started with an overview of how archival content traditionally makes its way online.

Start with a box -> described by finding aids -> digital copies of finding aids put on line and cherry picked individual items are digitized to be featured online.

Two Audiences, Two Sites

CDL has taken a new approach. They have two sites for two very different audiences:

- Online Archive of California (OAC): presents both finding aids and digitized primary sources and targets archivists, historians & researchers

- Calisphere – only takes primary sources (for now) and targets k-12 teachers, lifelong learners, and undergraduates

Collections can have home in several places. For example, the items about the Chinese in California can be found in:

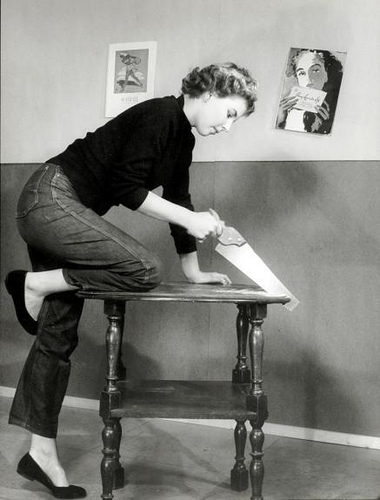

Calisphere has created themed collections to highlight superstar digital objects. They pull images out of the finding aids and rearrange them for the target audience. These images are hand picked and associated with an essay. They pick striking objects with good metadata. This is what their audience wants – the teachers asked for it. Another example themed collection is the Goldrush Murder & Mayhem collection which includes this photo of the “old time San Francisco pickpocket” Jennie Hastings.

Hidden Gems: Untitled and No Metadata

The next part of the presentation discussed what happens to items that are untitled and associated with no metadata. Lena showed us the results when you searched the OAC images for for untitled. I found 12,315 items when I did this search. They really only live in the context of the finding aid. Of course the challenge is that people use words to find images. These hidden gems can be helped by inheriting the metadata of their parent container (such as collection level information) when there is nothing else.

3 Approaches

- Digitize and release content to the web: low effort (after infrastructure is set up), very high return on investment. Over 40% of Calisphere traffic generated by google searches… but when users follow the link from google then they find the rich context.

- Align with other aggregators: – low/medium effort, medium return. Calipshere content is also being pulled into aggregators. They can also pull back new data that is added by 3rd party partners – such as reading level added on a teacher site. These are three examples of Murder and Mayhem content in three different partner sites:

- Cherry-picking the best items: high effort, promising returns – but it is also harder to measure the returns

Finding New Audiences and New Volunteers

The next step is to reach beyond standard cultural and education venues and move into different ares of the internet. For example, the CDL added links to Wikipedia. The perception of those involved with this effort was that it was a very convoluted process with lots of mysterious rules. They were unsure if the links would remain in place. It sometimes seemed like a lot of work when the links might just be removed. They added 33 links and found 53 links made by others not affiliated with the CDL. On the plus side, links like this puts the digital objects in a very specific context. Traffic initiated from these Wikipedia entries is almost certainly individuals seeking detailed information in the specific topic they are researching.

The next frontier involves blogs. CDL digital items are now featured in blogs, but soon CDL will be creating a blog for Calisphere to tell the story behind individual pictures. The final stop for this talk was an inspirational blog: Mustaches of the Nineteenth Century. This blog was presented as a way to achieve the fame that primary sources dream about.

Library of Congress

The second presentation, by Helena Zinkham from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division, was titled “The New Friends for Old Photos – putting pictures in your path with the Flickr commons and Web 2.0”. This talk focused on the pilot project of putting Library of Congress photos on Flickr in the new Flickr Commons.

People who want photos don’t think of libraries or archives. They go to museums and stock photo agencies. Helena wants to help people realize that archives are a great source of images.

There has been increasing progress with hidden collections. Lots of digitization and work with metadata has been done to help items make their way online. But this begs the question of whether we are just creating new hidden collections in corners of the Internet that the average person will never come in contact with. Collections like ArchiveGrid, DLF Aquifer, and OAC. The descriptions need to get out of the catalogs – most people find content on the web.. we need to put the images on the web in the path of the users.

The Flickr commons satisfied Helena’s desire to pull people in from Flickr back to discover the catalog world of archives. Flickr can be considered a virtual reading room and platform for a virtual volunteer corp. Helena showed the example of the image Weavers at Work. The comments on this photo included:

- information that photo is of blind women weaving rugs

- the photographer’s great grandchild identified the photographer as Percy Byron

- the start of a discussion about what the cabinet or instrument might be shown to the far right of the photo

These commenters are new friends worth making!

Pros of Web 2.0

- make collection available

- gain information about collections – participatory description

- increase the visibility of specific photos

- win support for cultural heritage organizations

Risks of Web 2.0

- disrespect for collections (smart aleck chat)

- loss of meaning

- reduce revenue from photo sales

- excludes undigitized collections

- higher costs (more money and time)

- less chance for us to have fun as history detectives – other people are doing ‘our’ work

read powerhouse museums’ 3 month report about their experience. … Helena will post info about the nuts and bolts on the SAA site, but she also directed the audience to Powerhouse Museum’s Commons on Flickr First 3 Months Report.

Flickr Basics

Helena asked the session attendees who was familiar with flicker? Most of the room raised their hands. Who has accounts? Still good number. Who is adding archival content? A sprinkling of hands were raised.

Helena then explores Flickr basics and showed off the following neat search examples:

Logistics and Statistics

The LOC liked Flickr and felt it was a good fit because photographs are the main focus of the site. They did need one big change. Because LOC is not the owner or photographer (unlike most photo contributors), they needed a way to express that clearly. Flickr responded by creating The Commons. They also created a new rights statement of ‘no known copyright restrictions’ for members of The Commons to use. This is different from public domain. Flickr also appears (based on my hunt through the links) to permit each institutions in The Commons to link to their own explanation about what they mean by ‘no known copyright restrictions’. LOC deep links to a specific section of their Copyright and Other Restrictions page for Prints & Photographs. George Eastman House has a special George Eastman House & The Commons on Flickr page about copyright, as does the Brooklyn Museum.

Statistics from the first 6 moths on Flickr:

- 3,500 LOC photos posted

- 8 million views

- 30,000 favorites for 80% of the photos

- 14,000 Flickr members made LOC a contact

- 5,000 comments (3,300 people)

- 12,500 unique tags (59,000 total)

- 500 catalog records updated – Helena indicated that this could be considered a new kind of backlog, “but a backlog you can come to like”

- 20% increased traffic to p&p online catalog

There are 30,000 more photos from Bain News Service on the way, but they are only adding fifty photos a week. This number was recommended by Flickr as the largest they would want to push at any one time. This goes back to the tolerance of people who have Flickr in their friend photo stream. Fifty photos is about as many as people want to get at any one time. More than that and you increase the likelihood that people would remove you from their stream instead of be overwhelmed. They would have no chance to really look at more than that.

Contributors to The Commons can choose which features to enable. For example, the Portrait of Hine as small child standing by drum shows how george eastman house chooses to send people back to their institution for prints.

How much does it cost?

- a Flickr pro account costs $24.95 a year

- digitization costs

- time: daily moderation on the account – LOC checks every day for uncivil discourse which takes about 10 minutes

- 15-20 hours a week to pull data from comments to update metadata

Flickr Comments

One of the greatest parts of this presentation was the examination of ways in which flicker users contributed through comments. Here are some examples:

- Auto Polo: – comment includes link to an auto polo thread on the Jalopy Journal’s message board which includes newspaper images and an extended discussion.

- Sylvia Sweets Tea Room – includes a very extensive history of the business added by the daughter of the original proprietor

- Negro boy near Cincinnati, Ohio – the comments include a deep conversation about the title of the photo and the context of this title at the time it was taken (1942 or 1943).

- Jones Barn where dynamite was found – Flickr members found the context and news article to go with this photo

- Al Palzer – this photo’s original title was Al Palser – but the misspelling was pointed out in the comments. The comments also include a response from the LOC noting that the boxer’s name would be updated in the original catalog record.

Other Promotion Approaches

The Library of Congress has now started linking out from the LOC catalog entries to the Flickr image so that it is easy for users to discover any conversations associated with the Flickr version. Powerhouse museum has a Photo of the Day blog to highlight images from their collection. The Brooklyn Museum encourages people to upload photos of things happening in Brooklyn. Then and now photos can be taken – in this case see factory buildings in Lowell, Massachusetts in December 1940/January 1941 and then again in January of 2008.

The key to 2.0 is frequent, new content and interaction from archival staff. Helena is open to new ideas about how to use Flickr and closed with saying that Web 2.0 is right in our path.

Questions and Answers

Question: What is their view of the accuracy/inaccuracy user generated tags and comments?

Answer: Study done in the past comparing accuracy of official cataloging to comments – even if people make mistakes, but others will correct them.. LOC has a ‘hands off’ policy to not delete/change stuff unless it is defamatory or spam. Only 3 instances of this so far. LOC is citing the source as ‘Flickr commons’ and also include commenters’ sources – which are actually a lot more varied than you might expect (like the Jalopy Journal).

Question: Are you worried about an increase demand in staff time as you add more photos?

Answer: Yes.. there will be an increase in demand.. but the Flickr comments are there and since LOC is adding links back out to those records they are available for researchers even if they are not added to the original catalog record. Maybe they need more staff? depends on goals. Could work with expert teams and look for ‘formal trusted’ volunteers. A great example was the baseball history association who took photos and contributed expert information in a spreadsheet (if I heard correctly they gave LOC a spreadsheet identifying team, game, date and opponent for more than 3000 photos).

Question: Isn’t the link from the LOC catalog record to Flickr enough? Why update the LOC catalog records at all?

Answer: They are really only updating when it is a mistake (like Palser’s name mistake). Flickr also provides APIs and LOC pulls all the comments and tags into external database so that LOC can choose how to use the information over time.

Question: What are your thoughts and concerns about the longevity of Flickr as a platform?

Answer: What grows fast can die fast. Their perspective: Flickr is a copy.. and LOC has an extract of all the tags and comments – nothing lost if it disappears.

Question: Calipshere: how do they work with teachers to learn their needs and their satisfaction with the work that is done?

Answer: They hired Berkeley experts to talk to teachers about what they wanted. They used interviews and created personas to capture the audience needs. Targeting the K-12 audience was aimed at being a success by being clear about their audience. Teachers used to print out images, but now they do more with powerpoint and iPods plugged into TV in the classroom. The teachers say they are happy with the theme collections and they want more. They have an advisory board with teachers.. they use surveys and watch the bboards.

Question: Is there a crossover between Calishpere and OAC users?

Answer: They almost didn’t cross link to the finding aids from within Calisphere.. but they decided the information was so important. Reason for the upcoming blog – want to tell the story behind the photos.

Question: Do they have anlytics/evidence of pulling people back to their sites?

Answer: Yes.. they can see increases in usage from everything they have done.

Question: When you download the comments – are they dated so you can only look at the new ones? How hard was it to change the title in your catalog?

Answer: Everything is time/date stamped when you pull info out of Flickr. Quick and easy to update.. 10 minutes per picture to do the updates.. Flickr members are doing a great job with citations.

Question: Do you have advice about how to get historical society folks who are concerned about loosing the admission fee for people coming in to do research on board with these web 2.0 approaches?

Answer: You show them alternative revenue streams. In the museum world .. they realized that they weren’t making money from reproductions and a change is in process to let people use images for publishing.. all about improving the brand recognition. Helena: I would love ideas from people using Flickr.. and to hear from people who are dealing with multiple audiences.

Question: Have you had complaints? Any specifically from copyright holders?

Answer: Yes.. they have had complaints.. one “Why haven’t you cleaned up the photos?” LOC position is to provide the version they have.. and it is up to others to cleanup and do what they like with the photos. They also point out that instead of perfecting photos, they are spending money on providing access to more photos.

Question: Expectations of service. Are people expecting that if they ask a question about a photo that they will get an answer from a LOC representative?

Answer: Do you have to respond to everyone who asked to be a contact? No.. perhaps different expectations for institutions. They currently add a comment when they are updating the original catalog records. Might acknoledge big contributors (more than 10 photos) at the end of the pilot via a direct e-mail to individuals.

Question: Have people complained about rights – that is my grandmother.. don’t put it on the web?

Answer: No. They do have a policy in place. Most people are ‘pleased as punch’ to learn that their family heritage is alive and well. OAC: They haven’t had anyone ask to take the content down. In the case that people provide feedback for updates – since OAC is an aggregation of items from so many institutions – they have to pass corrections info along to original keeper of the metadata and leave it in their hands to do updates.

Question: Is there a fear that interest will decrease as more photos are added to the commons?

Answer: Bloggers in the web were in love with the idea that the photos would go into Flickr. There was a big peak at the start – but views and comments are still steady (but smaller) . The more additions.. more communities that will be touched. The Powerhouse Museum experienced a tripling of their traffic after posting images in the Flickr Commons.

Question: Have people come into the reading room because of the Flickr pilot?

Answer: Maybe? We don’t know. Lena said she did!

Question: Are we teaching the teachers how to teach with photos?

Answer: Calisphere has provided links to info about using primary sources and analysis tools.. resources for teachers. (Follow-up: Are they clicking those links? Good question!)

Question: Are you contacting the people who post negative comments?

Answer: Yes.. and most of them were more spam.

My Thoughts

Culture of Online Communities

There are a few different ideas I wanted to share related to the material from this presentation. First, I noticed that the online culture of both Flickr and Wikipedia were called out as having a clear impact. They are in fact two very different communities. In the case of the LOC and Flickr we heard that part of what seemed to keep the comments constructive and friendly was that Flickr’s users strive to keep a ‘play nice’ atmosphere in place. In contrast, we heard that Wikipedia was perceived as confusing and unpredictable when the CDL staff was updating pages to add links back to their primary sources. They never felt certain that the links they were working so hard to add wouldn’t be removed the next day.

These are just two examples of ways in which the archival community is beginning to bump into various online communities. We need to really understand the cultural rules for each of the communities in which we want to participate. Another excellent example of this was the revelation that LOC should only upload 50 new images a week into Flickr because of the way in which users view new images uploaded by their friends. It would be unfortunate for LOC to loose many of its Flickr friends because it overwhelmed their Flickr feeds with 1,000 images.

Personas: Targeting Real People

I was also very pleased to hear Lena discuss the creation of personas to define and target the audiences they want to serve. If you want to listen to a great presentation on personas – give a listen to the IA Summit 2008 presentation Data driven design research personas (2nd podcast down on the page) while going though the presentation slides up on slideshare. I promise it is a very accessible talk (ie, low on jargon and tech – high on real life examples) and very worth your time. It was one of the best sessions I saw at that conference.

Finding Images Without Words

While today it is generally true that people must use words to find images – someday people will be able to use images to find images. An example of this work in progress is an experimental service named retrievr. You can already use this tool to search for Flickr images either by uploading an image or by creating a sketch you want to match. Another interesting image search interface is found over on Xcavator.net. You pick a photo as your starting point – and then you can even trace a subsection of the image to be used for subsequent image matching. We are not there yet – but we will be someday. I can only image the number of Untitled images that will finally be found!

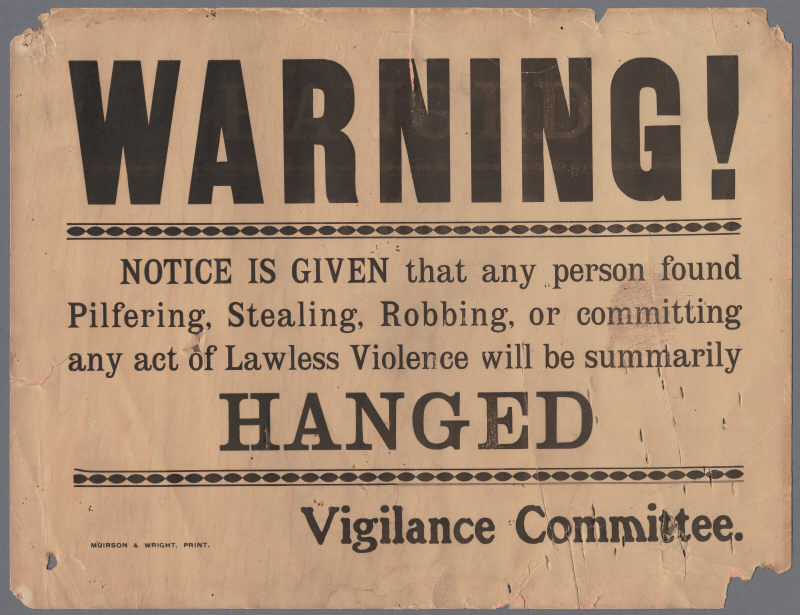

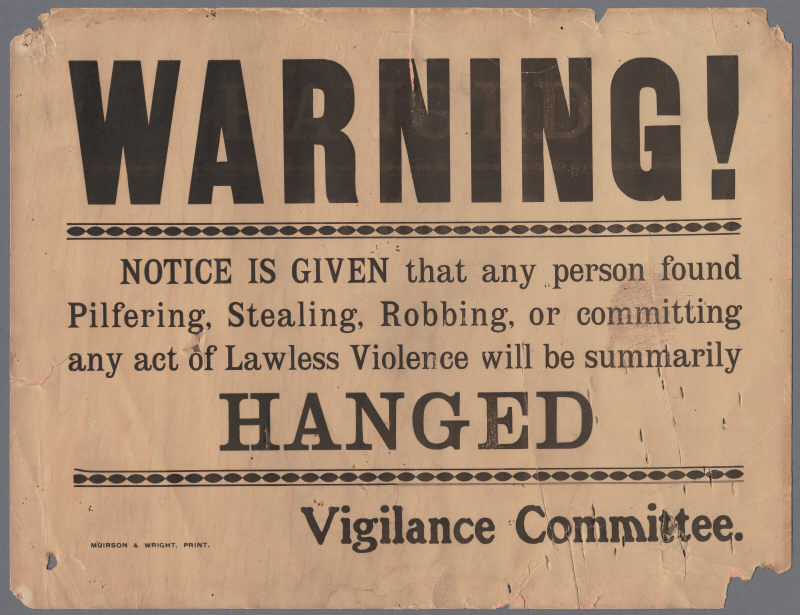

Vigilance

Your reward for reading this far is discovering my rationale for using the image I included at the top of this post. I think that many people are worried that we must be like the San Jose Vigilance Committee of 1906 – on our guard to stop people from stealing images from cultural heritage institutions when they are posted online. I would argue that the two projects described in this session show the benefits of a more open attitude. The Internet isn’t the wild west anymore. We should stop treating it that way. We don’t need Vigilance Committees online – we need ambassadors, interpreters and brave pioneers like Lena, Helena and the amazing teams of people who made the projects they described come to life.

Image credit: History San Jose Research Library via Calisphere.

As is the case with all my session summaries from SAA2008, please accept my apologies in advance for any cases in which I misquote, overly simplify or miss points altogether in the post above. These sessions move fast and my main goal is to capture the core of the ideas presented and exchanged. Feel free to contact me about corrections to my summary either via comments on this post or via my contact form.

Bio:

Bio:

The

The